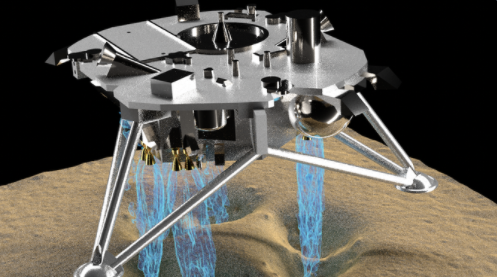

is about to launch. When it lands in February 2021, it’ll kick up a lot of red, damaging dust. (Image courtesy College of Engineering)

As the Mars 2020 launch approaches, a separate effort is using simulations to understand landing dynamics for tomorrow’s missions.

Future spacecrafts bound for the moon or beyond will benefit from high-powered computer simulations underway at the University of Michigan that model the particulate mayhem set in motion by rocket thruster-powered landings.

During descent, exhaust plumes fluidize surface soil and dust, forming craters and buffeting the lander with coarse, abrasive particles. This action presents a host of variables that can jeopardize a landing. Our current understanding of those millions of interactions is based on data that is, in some cases, 40 to 50 years old.

Toward advanced physics-based predictive models

Much of the modeling work is performed on Great Lakes, U-M’s newest high-performance computing cluster. That allows the research team to partition the problem over hundreds, and even thousands, of processors simultaneously. Therefore, each processor does a portion of the work and only needs to store a small fraction of the total data.

But even the most powerful computers in the world right now can only resolve so many of these interactions. To go deeper, Capecelatro uses models—best guesses based on all available data—to push the simulations further. The goal is to provide a framework NASA can use to better predict how different designs will impact the ground and the landing, and adjust.